Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR uses infrared spectroscopy to create an absorbance signature of organic compounds, including those recovered from archaeological sites. These signatures, or spectra, may then be compared with both commercial and private libraries of the spectra from known material to identify the unknown organic compound. Over the past several decades, the FTIR has been used to identify contaminants in manufacturing environments, for material quality control, and as a forensic tool for law enforcement agencies. PaleoResearch Institute is now among a handful of facilities in the world who are using the FTIR to identify archaeological food remains and organic components in sediments from archaeological sites. We have examined ceramics, nutting stones, and fill from fire features and have found the FTIR to be a practical, economic tool to identify di- and tri-glycerides from meat fats, nut oils, maize, and a variety of plants.

What questions can FTIR answer?

What foods were cooked in this vessel or feature?

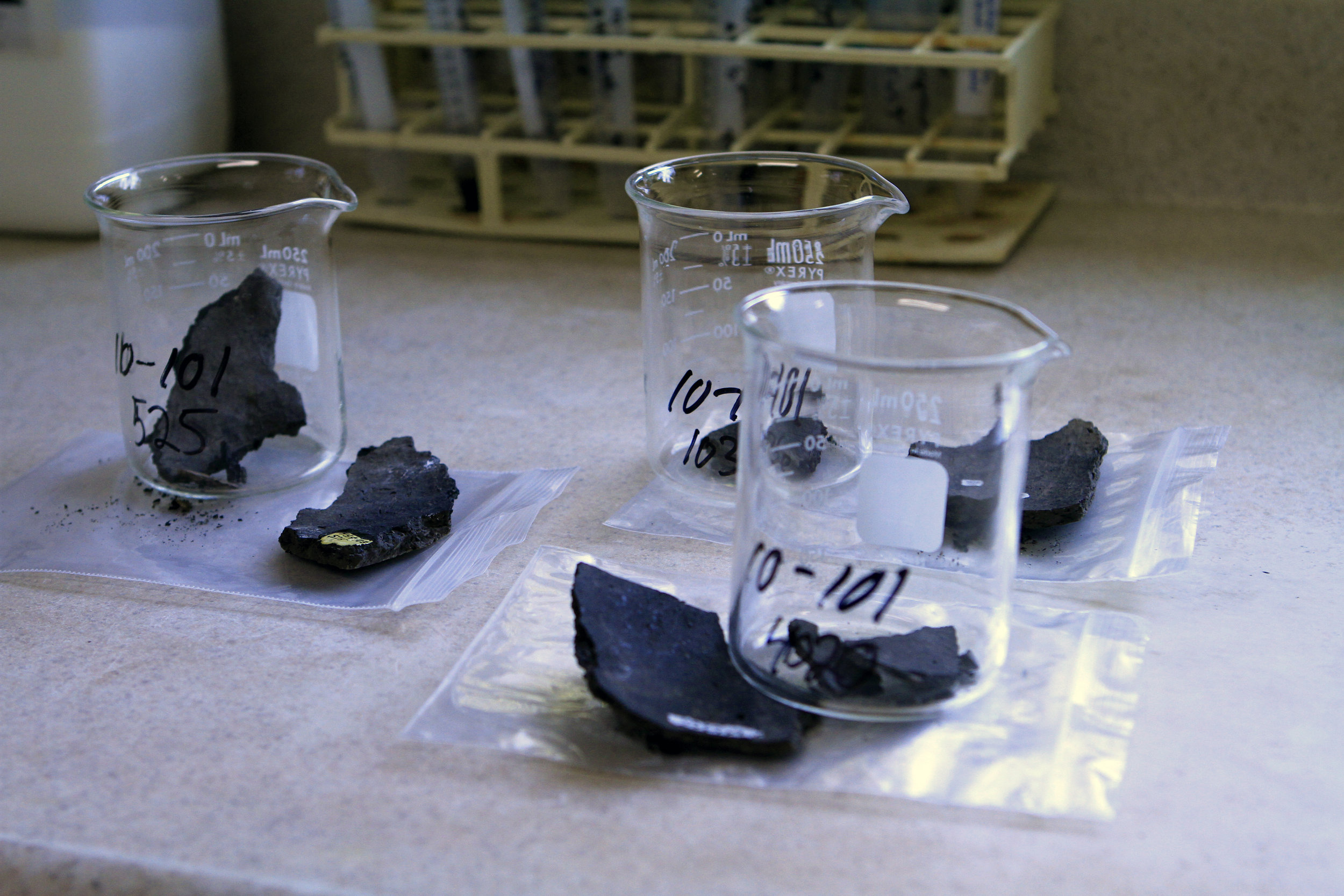

Fats, lipids, proteins/amino acids, and carbohydrates/polysaccharides are released from vessels (or fire-cracked rock or sediment) with a solvent (a high purity chloroform/methanol mixture). Peaks (by wave number and amplitude) representing these compounds are compared with our commercial and proprietary reference collections to identify types of categories of foods and medicines prepared.

What was processed with this tool?

Nut oils and residue from grinding and abrading surfaces can be extracted and compared to our libraries. Although we usually cannot identify specific plants processed, analysis does provide a look at activities such as nut oil extraction.

What was processed in this feature?

Sediment fill, charcoal, fire-cracked rock, and sediments from living surfaces can be analyzed to identify feature use or define activity areas within features or structures.

Feature Fill:

The sample should be taken from fill that includes cultural material, i.e., burned remains (but not the fuel layer). We have examined feature fills from several locations. For instance, a pit in northwestern Colorado yielded evidence of meat fat in the form of matches with mono- and diglycerides from meat.